The Salvo, vol. 2: What are intellectuals good for?

Surviving the post-Bowie age and marriage advice from Stuart Hall.

Welcome to the second edition of The Salvo, your weekly newsletter about ideas from the New Statesman. This week: Stuart Hall and the intellectual profile.

If, as Maurice Bendrix declares in Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair (1951), a story “has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead,” then a good starting point for a history of the last few years might be 10 January 2016. That was the day, the day David Bowie died, that the world started going to s**t.

Good celebrities died – Ali, Castro, Prince & Co. – and a bad one became president. It was a minor extinction event that served as an overture for what followed: Brexit, Covid-19, populist insurgency, protest on the streets, trench warfare (with drones) in Ukraine – cardiac events played out against the climate emergency and widespread economic dysfunction. We scrolled through the carnage, liking, disliking, calling things “polycrisis” and quoting Gramsci. But as Mike Davis wrote shortly before his death in 2022, incantations to Gramsci’s notion of the interregnum “assumed that something new will be or could be born. I doubt it. I think what we must diagnose instead is a ruling class brain tumour: a growing inability to achieve any coherent understanding of global change as a basis for defining common interests and formulating large-scale strategies”. Gaza has been turned into a charnel house. After years of deferral, a more definitive reckoning with the postwar order and its intellectual foundations remains far off, but closer than it did on 9 January 2016.

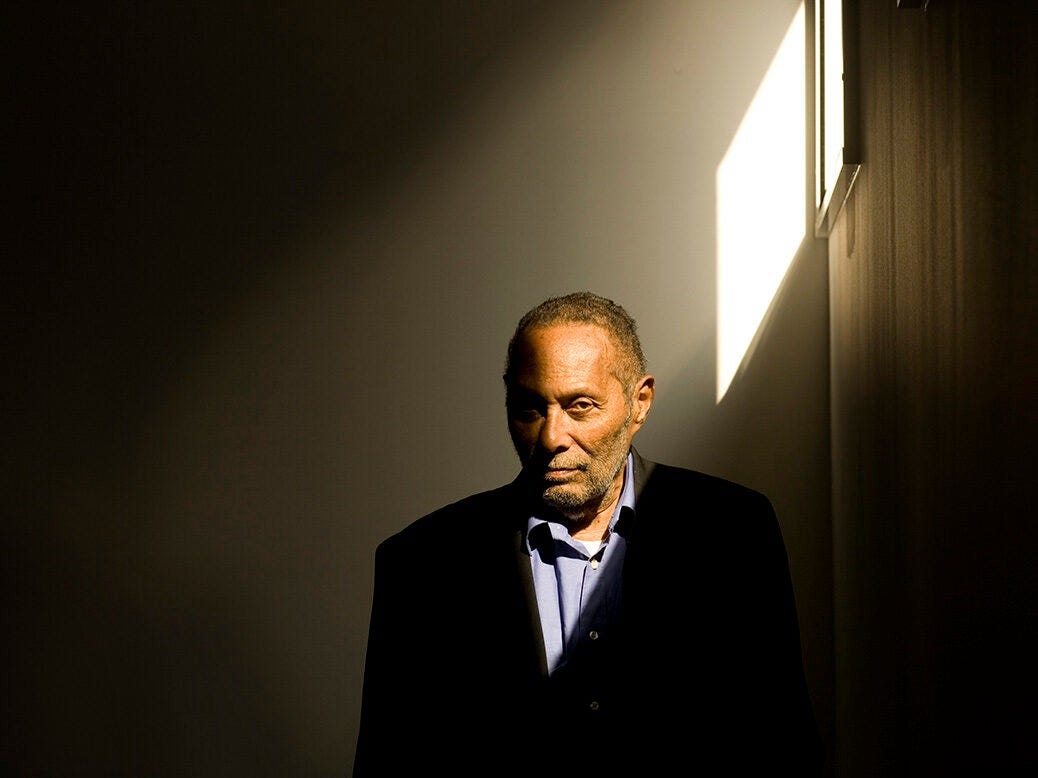

There are few thinkers I have returned to more regularly to try and comprehend the events and trends of recent years than the Jamaican-born cultural theorist Stuart Hall. Born in Kingston in 1932, Hall came to England in 1951 on a Rhodes scholarship. In an article for the 50th-anniversary of New Left Review, a journal that he helped found in 1960, he described how, allergic to the “casual confidence” of Oxford’s Hooray Henries, Hall found his fraternal bearings in the “rebel enclaves” of “demobbed young veterans and national servicemen, Ruskin College trade unionists, ‘scholarship boys’ and girls from home and abroad”. In 1956, within the political tempest that whirled on campus following the Soviet invasion of Hungary and the Suez crisis, Hall co-edited Universities and Left Review, which later merged with E.P. Thompson’s New Reasoner to create NLR. Some digging in the NS archives reveals that it was around this time that Hall contributed his first piece for the magazine: a review of a theatre production of Romeo and Juliet.

In 1964, Hall was appointed to the University of Birmingham, where he helped establish the discipline of cultural studies. It was from here that he started to reckon with the afterlives of “Powellism”, which he saw being reproduced – through moral panics about the breakdown of law and order, and the linking of daily economic hardship to the grander narrative of imperial decline – in the New Right. Hall coined this New Right “Thatcherism”.

What Hall saw emerging in the 1970s and 1980s – the enforcement of the market, the erasure of welfare provision, the criminalisation of the poor and precarious, the racialised view of crime and national security, military adventures abroad, jingoism at home, and the septic vapourings of a right-wing press – amounted to what he called a “philistine barbarism”. It was an apt phrase for describing the authoritarian populism of Thatcher’s time in office. But it also sums up the flag-waving communitarianism of New Labour and the cutlust of David Cameron’s neoliberal wrecking crew. It may even help us comprehend a Keir Starmer government when its time comes to administer the further enshittification of national life.

In ‘The Great Moving Right Show’ (1979), Hall advised the left not to dismiss the popular appeal of Thatcherism, nor explain it as a form of “false consciousness”. Thatcherism was more than statecraft but a project that, in Thatcher’s words, strove to “change the soul”. “Its success and effectivity,” Hall wrote, “do not lie in its capacity to dupe unsuspecting folk but in the way it addresses real problems, real and lived experiences, real contradictions – and yet is able to represent them within a logic of discourse which pulls them systematically into line with policies and class strategies of the right”.

Hall’s analysis of the New Right built on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, which reflected an appreciation of continental thinkers that began sometime in the mid-1960s. Looking back, scholars of Hall’s work have observed the shift from his interest in writing literary essays about the arts to the more theoretical work that drew on Bathes, Lévi-Strauss and Althusser. Until now the reason for the shift could only be guessed at. But the recent discovery in Hall’s archives of an unpublished manuscript, A Cure for Marriage (1968), exclusively reported in the NS last week by the journalist Donna Ferguson, may now provide the answer, shedding new light on Hall’s life and work.

As Ferguson explains in her piece:

[Hall’s “lost” manuscript] is made up of different analyses of a contemporary short story, “Cure for Marriage” by Nancy Burrage Owen, which had appeared in the magazine Woman. It centres on a dissatisfied middle-aged housewife who goes to the cinema and enjoys a fantasy about having an affair with Cary Grant, which somehow enables her to remain married to her passionless, unappreciative husband. Hall viewed this short story as essentially a case study of mass-market popular culture, and named his book A Cure for Marriage: A Case Study in Method.

Hall realised that the usual intellectual approaches weren’t adequate to excavate any deeper meaning from Owen’s story, and what it revealed about mass popular culture, and so in A Cure for Marriage he turned to European schools of thought for the first time to help him.

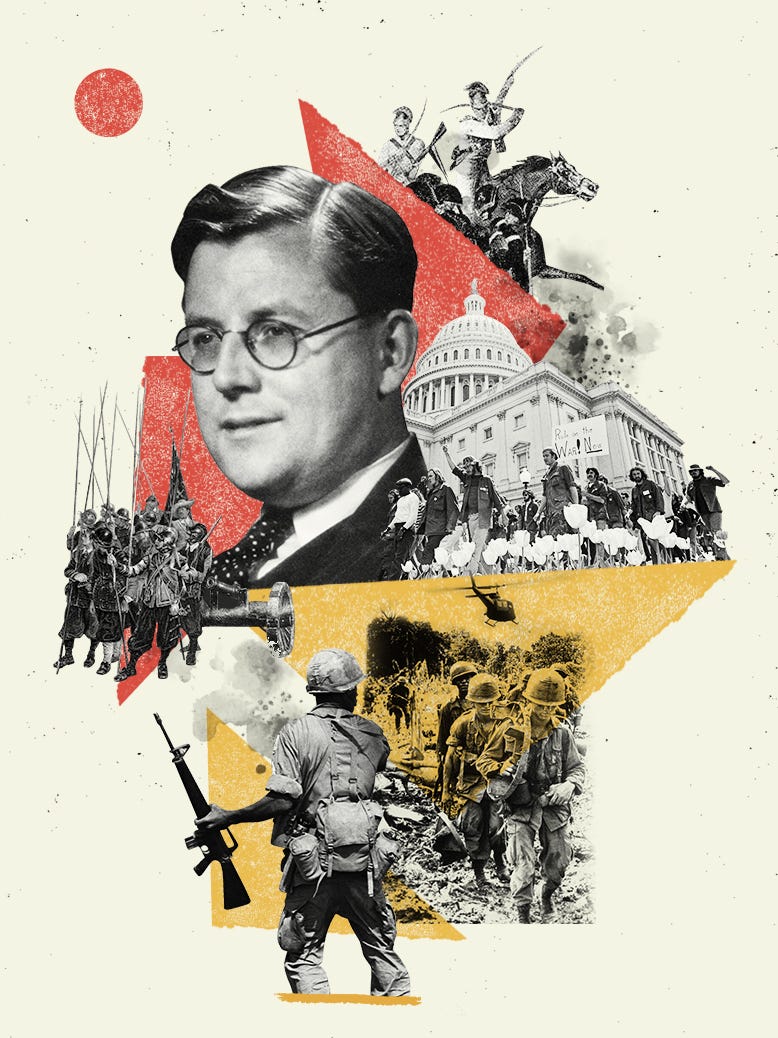

Since joining the NS in 2019, one of the things I’ve tried to do is help make the magazine the home of the intellectual profile. An early commission for the title was an essay by Nikhil Pal Singh on the 20th-century American thinker Randolph Bourne. Since then, I’ve worked to expand the gallery, which now includes, among many others, deftly worked portraits of Tom Nairn, Mark Fisher, Wittgenstein, Simone Weil, Patrick Deneen and Yoram Hazony, Elizabeth Anscombe & Co., David Harvey, and Martin Heidegger.

The profiles written by Madoc Cairns for me during this time – on Jacques Maritain, Leszek Kolakowski, E.P. Thompson, Mario Tronti, and most recently J.G.A. Pocock – have elevated the genre of intellectual history to new heights of style and insight. As Lee Siegel, one of my favourite critics and someone who knows a thing or two about good writing, put it to me after reading Madoc’s work: “every word is sacred for him. Every turn of phrase is unique and cared for. Caring, that’s it. That is what makes the freest most inventive language moral. And the gift of absolute attention to the thing itself. ‘How beautiful it is, that eye-on-the object look,’ as Auden put it”.

The latest intellectual profile is a superb essay by Nicholas Guilhot on the ideas of the 20th-century Italian philosopher and historian Ernesto Di Martino, whose preoccupation with how we should think about the Apocalypse is all-too pertinent for our Bowie-less age.

Readings from the NS

“No one seems to know any more just what American power is, what its function is, how it should operate, what its basis is in either morality or raison d’état. When Biden froze, in what looked for all the world like terror, before a chaotic room animated by self-interested reporters, each one guided by their own agenda, he might have been confronting a world that is on fire”. Lee Siegel sees in Biden a “hologram president” who is fading like American power itself.

The proliferation of online pornography has degraded the way we view our bodies and relationships, writes the author and NS columnist Megan Nolan in a superb piece on sex in the age of digital desire.

“It remains to be seen whether JD Vance can advance, as a matter of policy, the kind of conservative social-democratic instinct that came naturally to his Appalachian kin”. Sohrab Ahmari interviews the Ohio Senator, and possible Trump Veep, JD Vance.

I’ve interviewed John Mearsheimer on the enduring power of the Israel Lobby and how badly it’s going for the US and its allies, well, just about everywhere. This follows on from a longer profile I wrote of the Chicago IR scholar last year.

Reading and listening elsewhere

Stuart Hall, ‘The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left’ (Verso, 1988). These essays are a good place to start if you’re new to the work of Stuart Hall and feel as bracing and urgent as they were back in the 1980s.

Terry Eagleton, ‘Seeds of What Ought to Be’, London Review of Books, Vol. 46, No. 4, 22 February 2024. In November last year, we published an extract from Richard Bourke’s long-awaited opus on Hegel. In his review of the book, Terry Eagleton detects a conservative critique of the idea of revolution. “Hegel’s World Revolutions”, Eagleton writes, “displays a knowledge of its protagonist’s thought which may well be unequalled in Britain. Its mountain of secondary sources is just as impressive. The ingredient it lacks is criticism. In nearly three hundred pages, scarcely a single negative judgment is allowed to besmirch the good name of the master. This suggests that something rather more is going on here than an anatomy of Hegel’s political thought. Lurking beneath this account is a political animus that never really speaks its name. It would be good if it came out into the open.”

‘Project 2025: Building a “Better” Trump Administration’, Know Your Enemy, 30 January 2024. My favourite podcast. In KYE, co-hosts Sam Adler-Bell and Matthew Sitman provide a leftist's guide to the US conservative movement – its history, personalities, ideological foundations and current trajectories – with intellectual rigour and open-mindedness towards their “enemies” on the right. This episode explores how conservatives and their think tanks are preparing for a second Trump administration. It’s a must-listen for understanding what Adler-Bell has called “the shadow war” to determine who will staff a new Trump presidency.

The historian RJ Evans shares his unbeatable review of ‘The Zone of Interest’.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

— Gavin.

Sorry, I'm a bit lost. Did the writing on Stuart Hall's 'A Case for Marriage' actually end when it did or am I missing something?