The Salvo, vol. 3: Liberalism's last laugh

Inside: Kaputt, The Wanderer, a communist enters the Panthéon, and is Trump funny?

Welcome to the third edition of The Salvo, your weekly newsletter about ideas from the New Statesman. This week: a book, a painting, and a joke.

On the evening of 16 February, after my colleagues had left the NS office for the weekend, and while waiting for a contributor to file some late copy on the death of Alexei Navalny, I finished the most profound reading experience of my life so far. “In Naples we also have struggled against the flies. We have actually waged war against flies. We have been fighting flies for the past three years.” “Then why are there so many flies in Naples?” “Well, you know how it is! The flies have won!” So concludes Curzio Malaparte’s Kaputt (1944), a genre-defying work of surrealist reportage based on his wartime experiences on the Eastern Front as a correspondent for the Italian newspaper Corriere della Serra.

In Kaputt, Malaparte – vain, elitist, and a disaffected supporter of Mussolini – describes his excursions through countries occupied by the Axis, including Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, Poland, and the Baltic states; he also visited Romania and Finland, both allies of Germany, and neutral Sweden, with a brief stint in Berlin.

There is something Proustian in the way Malaparte stays in a scene, refusing to look away no matter how macabre the spectacle or ugly the person, recounting his real, as well as invented, encounters with Nazi high commanders, Swedish princes, Moldovan prostitutes, German soldiers, Italian diplomats, Jews enslaved in ghettos, dead horses suspended in frozen lakes, dead soldiers frozen upright in snow, and the occasional ghost. He witnesses a pogrom in Iaşai, enjoys a sauna orgy with Himmler, parties with Hans Frank and Poland’s fascist aristocracy, rescues a friend trapped under an avalanche of dead bodies disgorged from a cattle-cart, and watches war dogs trained to carry explosives run under Panzers and blow them up. Reading Kaputt is as close as you’ll get to stepping into a hellscape by Hieronymus Bosch.

Although many of the grotesque scenes and vignettes that compose Malaparte’s chronicle are embellished and fictitious, there is a truthfulness to it all since the exaggerations bring into sharper resolution, in a way non-fiction often can’t, the extreme savagery and methodical violence that unfolded across Europe’s killing fields between 1939 and 1945, and the way, as Malaparte quotes Montesquieu, “there came forth from the soil armed men who exterminated each other”.

I don’t want to write too much more on Kaputt –I’ve asked my colleague Will Lloyd, a gifted writer who (and he may not thank me for saying this) is probably the only person I know who can get inside Malaparte’s head and make sense of it all, to write on the book next week. Kaputt’s 80th anniversary will coincide with the two year anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which seems a good enough reason to return to Malaparte’s text.

But what struck me most about Kaputt was not just the Italian’s gift of observation, such as his description of a young Gestapo officer – the nameless “Himmler’s man” – he sees at a dinner party:

I felt as if I saw him for the first time at that moment, and I was startled. He was looking at me, too, and our eyes met. That man was in his middle years, not more than forty; his dark hair was already graying at the temples, his nose thin, his lips drawn, and pale, his eyes extraordinarily light. They were gray eyes, perhaps blue or white, like those of a fish. A long scar cut across his left cheek. Suddenly something began to worry me: his ears; they were extremely small, bloodless, waxlike, with transparent lobes – the transparency of wax or milk.

[…]

There was something softish, almost naked in the Gestapo man’s face. Although his skull was strong and rough hewn, and the bones in his forehead looked solid, well-knit and extremely hard, the face seemed, nevertheless, that it might give way at the touch of a finger, like the head of a new-born babe; it looked like the skull of a lamb. His narrow cheekbones, his long face and slanting eyes were also like a lamb’s; there was something at the same time bestial and childish in him. His brow was white and damp, like a sick man’s; and even the perspiration that feverish sleeplessness brings to the foreheads of consumptives as, lying on their backs, they await the dawn.

[…]

He gazed at me in silence, and, by degrees, I perceived a strange smile, shy and very sweet, playing on his thin, pale lips…I suddenly saw that his eyes were empty: he did not listen to the other words of the guests, he did not hear the sound of voices and of laughter, the tinkling of forks and of glasses – he saw transported into the loftiest and purest heaven of cruelty – that “suffering cruelty which is the true German cruelty – of fear and loneliness. There as not shade of brutality in his face, rather something shy, vague, like a wonderful and moving loneliness. His left eyebrow was raised at an angle that loftily expressed cold contempt and cruel pride. What knit all his features together, all the traits and the tricks of his face, was that suffering cruelty, that wonderful melancholy loneliness.

After a time it seemed to me that something began to melt in him, something alive and human – a light, a colour, perhaps a look, a child’s look, was being born deep down in those empty eyes. He seemed to me to be swooping down as gently as an angel from that lofty, remote and very pure heaven of his; he came down like a spider-angel, gliding slowly along a very high, white wall. Like a prisoner escaping along the sheer wall of his jail.

What also struck me were the frequent references to laughter. Amidst the cruelty, on almost every other page, people – the Nazis and their coterie of lickspittles and replicants – laugh in a way that intensifies the bestial atrocities they commit on all those around them. It is a world, as one of Malaparte’s friends puts it, of “smiling monsters”.

I’ve been thinking about laughter while working on a new piece on laughter and liberalism from the American critic Lee Siegel. Lee has also been thinking about laughter, and its status in a democracy, since the publication of ‘Why I Am a Liberal,’ an essay that appeared in the New York Times in November last year by the Harvard constitutional scholar Cass Sunstein. As Siegel writes, “leave aside Sunstein’s 34 reasons—34 exactly—for being a liberal, which are more like 34 reasons to give up on liberalism altogether, what struck me was Reason Number 30: “Liberals like laughter. They are anti-anti-laughter.” That might have had them rolling on the floor in the faculty lounge, but it left me scratching my head”.

For Siegel, laughter is a crucial subject for a democracy to take seriously. Indeed, the fate of democracy could well depend on what makes us laugh. In the US, Trump’s inventory of monikers for his enemies is so long that it has its own Wikipedia page (my favourites are probably those for Jeb Bush – ‘Low Energy Jeb’ – and Justin Trudeau – ‘Justin from Canada’). I asked Lee if he thought the ex-president-cum-GOP-frontrunner was actually funny.

“Well, we have to make the distinction between Trump being so ludicrous that he makes you laugh and other people satirising his ludicrousness and making you laugh. When he was out of power, he was harmlessly ludicrous and you could laugh at his most outrageous outbursts of vanity. That was stage one. When he became president, you searched for satiric portraits of him to relieve the rage at seeing him in office – enter Alec Baldwin chiefly, and most successfully – but also legions of other comedians. That was stage two. Now, as he poses a mortal threat to America that he never did before, nothing he says or does provokes laughter. And he is beyond being satirised for the purpose of provoking laughter. He is too close to menace to be funny.

“The problem with treating Trump as comedy has always been that holding aberrant behaviour up to laughter also socialises it and thus normalises it. The other thing about irreverently mocking Trump is that, to the extent that irreverence occurs outside the borders of what is normative, Trump, being a sociopath, makes any mockery of him also redundant with who he is. I find jokes mocking Trump to depressingly reiterate his nature and amplify it. Beyond being too dangerous to be funny – too mendacious and rhetorically brutal – he is too absurd to be funny. The Latin root of absurd is ‘deaf’. Trump's absurdity reduces life to silence.

“If one of the functions of humour is to expose what is hidden or what not to be acknowledged or talked about, then Trump, whose preposterousness and danger are transparent, has now travelled far beyond the region of humour. What did Nietzsche famously say, that a joke is an epigram on the death of a feeling? Anyone who laughs at Trump is laughing at what he embodies, which is the death of human feeling.”

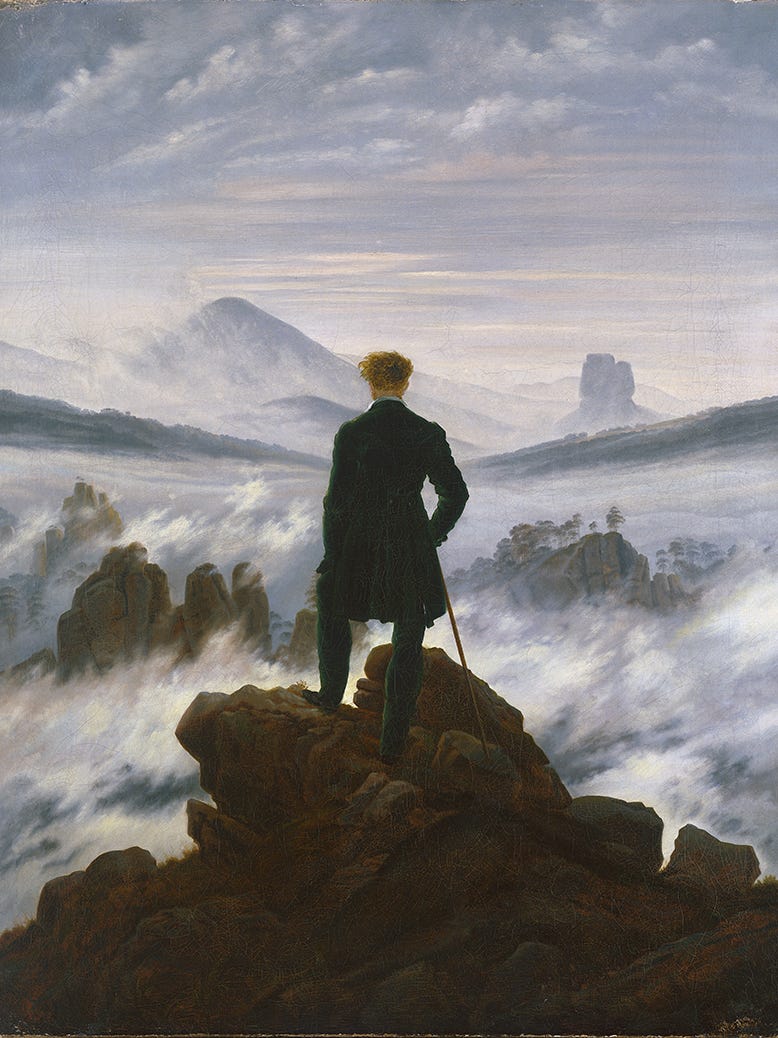

Before I joined the NS, I was a postgraduate working on the history of ideas. In my first week as an undergraduate, I saw a course being advertised on the history of political thought from Plato to Fanon. What ignited my curiosity was not so much the names, which I had barely encountered, but the image that illustrated the course – Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. I don’t think an image has become so intimately associated with the history of ideas. Hardened into cliché through endless reproduction and circulation, the painting is a stock choice for publishers who want to market volumes by Shelly, Byron, and Nietzsche, and has been used to illustrate more recent works such as Hari Kunzru’s novel Red Pill (2019).

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Friedrich’s birth, so I asked the intellectual historian Peter E. Gordon to write on The Wanderer. Gordon isn’t a fan: “The first time I saw his painting, nearly 40 years ago, the word that came to my mind was kitsch. It was Hermann Broch who once defined kitsch as ‘failed Romanticism’, an apt definition, perhaps, if only because it conveys the sense that kitsch wants to be more than it is: it aims for spiritual heights, but on its way to the mountain peak it stumbles and becomes an object of derision.”

Such aversion only serves Gordon’s essay, which expertly draws out the historic and contemporary political import of Friedrich’s most famous work.

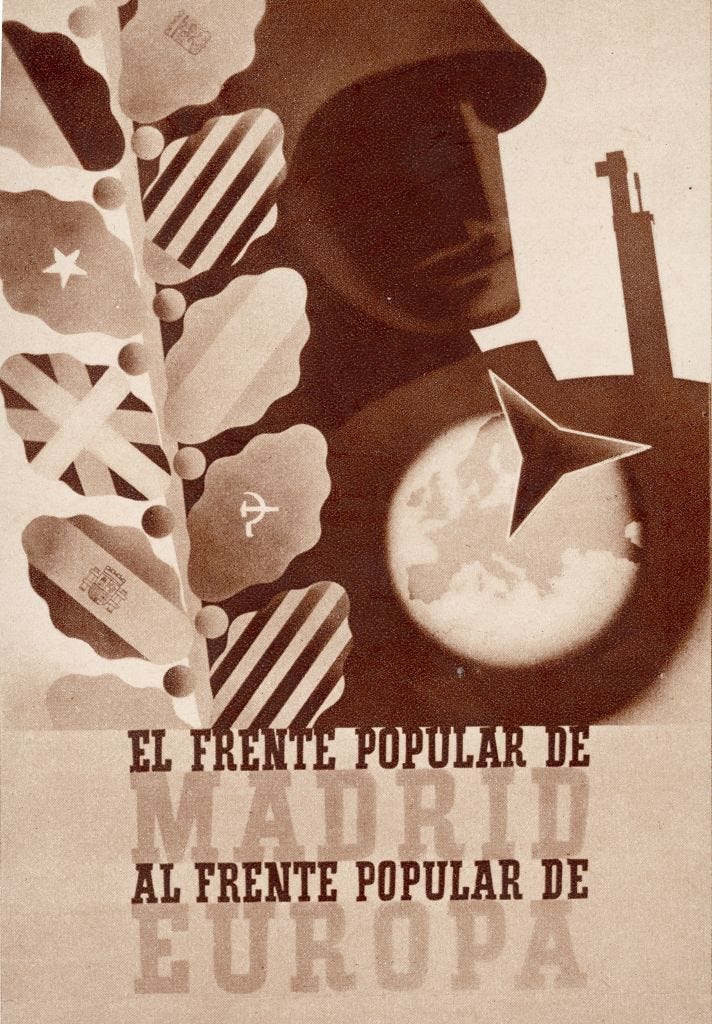

My postgraduate research ultimately focused on the concept of fraternité as exemplified by those groups and individuals who crossed Europe’s borders between the 18th and 20th centuries in the name of liberty, from the French Revolutionaries to the International Brigades and the Resistance against Nazi-occupied Europe. So, it was especially pleasing to see that on 21 February, Missak Manouchian, an Armenian who joined the French Resistance in 1943, has been laid to rest in the Panthéon. He is the first foreign Resistance fighter and the first communist Resistance fighter to enter France’s hallowed mausoleum.

Back in 2022, when she was still Foreign Secretary, Liz Truss declared her support for anyone who volunteered to fight with Ukrainians against Russia’s invasion of the country. By doing so, she unwittingly joined the annals of radical internationalism, a figure in league with past revolutionaries such as Maximilien Robespierre, Giuseppe Mazzini, Maurice Thorez, Ho Chi Minh and Jean-Paul Sartre. Her comments about Ukraine evoked a forgotten history, what Robespierre in the 1790s called “the obligation of brotherhood”: the necessity of thinking about one’s own liberty in relation to the liberty of others.

The most famous example of this ideal is the International Brigades. Formed during the Spanish Civil War, the Brigades consisted of around 35,000 people who travelled to Spain from more than 60 countries to fight in support of the anti-fascist forces. Like Ukraine, Spain stood at the political periphery of Europe, but between 1936 and 1939 it became a crucible in which the political and ideological confrontations of the preceding 20 years — nationalism vs internationalism, modernity vs conservatism, proletarian vs proprietor, democracy vs fascism — reached a crescendo in Europe’s decades-long civil war.

It wasn’t just in Europe that people saw their own freedom as being linked to the enjoyment of freedom (or its suppression) elsewhere. As the historian Tim Harper shows in Underground Asia (2020), anti-colonial movements from the early 20th century were guided by Asian radicals who were multilingual, steeped in the ideas of anarchism and Marxism, and who regarded the struggle against empire as a truly transnational undertaking. Through their collective struggles against British, French, Dutch and Portuguese imperial authorities, radicals came to see “Asia” as a single field of revolution. Many believed that the post-imperial future would be a borderless world.

This link between combat and political vision was especially pronounced in the French Resistance. From the mid-1930s, the rise of fascism forced many people to leave their countries and seek refuge in France (hardly the free and fraternal sanctuary that many had hoped). It was from France that Italians, Spanish, Austrians, Czechs and others took up arms to liberate Europe from fascism. Some of the most daring acts of sabotage, ambush and assassination against the German occupiers were carried out by foreigners such as the Manouchian Group, which was comprised of Hungarians, Italians, Poles and Romanians.

Most saw the struggle to liberate France as the first act in the liberation of their own countries. “For me, this war represents a continuation of Spain,” said one Spanish brigader fighting in the resistance. “I prefer the wide horizon of the battlefield than the limited space of the concentration camp, the fraternity of the combatant than the hostility of the fellow sufferer.”

The professionalisation of modern armies and the advanced weaponry deployed on the battlefield make travelling to fight as an aspirant resistant a lethal prospect. This is why the modern brigader is more likely to be someone sat in front of a computer wielding codes from a distance than manning a rifle on the front line.

In his essay “The Republic of Silence” (1944) Sartre wrote that “the choice each of us made of his life and being was an authentic choice, since it was made in the presence of death”. As Russian forces grind out victories in Ukraine, and Israel continues to rain down fire and steel on the Palestinians, there has rarely been a more urgent time in recent years to recall the traditions of fraternity and solidarity as exemplified by those like Missak Manouchian, a point of light in a world gone kaput.

Reading elsewhere

John Ganz, ‘Villa of the Damned’, Artforum, Vol. 61, No. 3, November 2022. The American writer John Ganz, a gifted reader and expositor of texts, wrote this piece about Casa Malaparte on the island of Capri. I hope to interview John in the coming weeks about his forthcoming book, ‘When the Clock Broke: Conmen, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked up in the early 1990s’.

Lots of people were slamming Rachel Cooke for her snooty review of the “very tall and very smart” Lauren Oyler and her new book of essays. Not enough people were talking about Becca Rothfeld’s brilliant essay for the New Yorker on sex, Cronenberg and consent.

One of the more significant works of social and political history to be published recently is the historian Gabriel Winant’s ‘The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America’ (2021). Tribune have published a howler of a review, a model of how to badly misread a book and the author’s intentions. A much better place to learn about the importance of Winant’s project on class in the 21st century is Amelia Horgan’s interview with him for Common Wealth.

In the latest issue of American Affairs, Alex Hochuli is the latest to give his post-mortem on the millennial left. This follows pieces by James Butler in the LRB and Will Davies for the New Statesman.

Reactions to The Salvo

I loved your account of your drink with Meaney in the first edition of The Salvo, which is a bracing breath of fresh air. I was listening last evening to my daughter practicing a Schubert Impromptu and thought of how much Germany haunts me. And having lived in Brooklyn for years before it became a mecca for little magazines, years when it was a low-rent paradise of young families, lesbians and liberal Jews, I cannot wait to read you on the subject.

Reading your ‘opening salvo’ from my sickbed and loving the format! A substantial and well-written piece, rather than just a run-down of articles.

Cool newsletter. Look forward to you calibrating the balance of ideas and drinking stories. Personally, I want more of the latter.

Technically, Myanmar Beer was Junta-funding, not Junta-funded. Excellent casual drop of the word ‘enchiridion’.

I am a woman of the political right, despite, so far, the current Establishment’s unremitting efforts to turn me into a foaming-at-the-mouth sans-culottes. I read The Saturday Read [our weekend newsletter] to help ensure that I am exposed to other outlooks on life, and don’t stay in my echo chamber. But honestly, ‘enchiridion’? Really? Is this a deliberate aim at the bullseye of Pseuds’ Corner? Could it be a word Gavin’s just learnt, and insists on deploying wherever he thinks he can get away with it? I have been that person in my youth.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

— Gavin.

Great to read these clips from Malparte's Kaputt. And congratulations to whoever translated him from the original Italian - these folk never get the credit they deserve, yet they can make or break an author's international impact.