The Salvo, vol. 4: American nightmare

Inside: Frantz Fanon, Ukraine's history wars, and Aaron Bushnell.

Welcome to the fourth edition of The Salvo, your weekly newsletter about ideas from the New Statesman. This week: Writers, missionaries, and militants.

Essays should teem with ideas yet exult in their own shortcomings, never striving for completeness or resolution. For Adorno, the essay desires “not to seek and filter the eternal out of the transitory; it wants, rather, to make the transitory eternal”. He put the point more succinctly: “The whole is the false”.

It was Mary-Kay Wilmers, the former editor of the LRB, who taught the American author Adam Shatz this rule, “and with her guidance,” he notes in the introduction to Writers and Missionaries: Essays on the Radical Imagination (2023), “I learned to resist the temptation to have the last word”.

In his subtle, if sometimes quiet, disquisitions on intellectuals such as Edward Said, Richard Wright, William Gardner Smith, Michel Houellebecq, Jean-Paul Sartre, Claude Lanzmann and others – essays all previously published in the LRB (where he is US editor), as well as in various US magazines – Shatz avoids entombing his subjects in cast iron accounts of their work or providing sanitised versions of their lives.

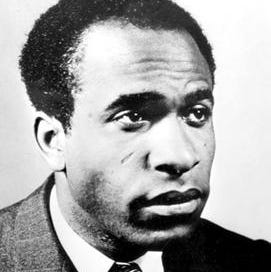

He has also just published The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon, an intellectual biography of the French and West Indian psychiatrist and revolutionary, whose best known work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961), was described by Stuart Hall as the “Bible of decolonization”. Writing in the mid-1990s, Hall asked: “Why Fanon? Why, after so many years of relative neglect, is his name once again beginning to excite such intense intellectual debate and controversy? Why is this happening at this particular moment, at this conjuncture?” That is our question, too.

Fanon’s world, the world of colonial empires and the Cold War, has gone. But its pathologies – racism, white nationalism, poverty, exploitation, psychological torment, and humiliation – endure.

The original backdrop to Shatz’s book was Black Lives Matter and the rebellions that forced a brief reckoning with what Malcolm X called the “American nightmare”: racial and economic injustice, carceral expansion, mass addiction, the high tolerance for violent civilian death, and the blowback from failed military adventures abroad in the form of hyper-militarised police forces at home. In the summer of George Floyd, Fanon became an intellectual lodestar for America’s wretched of the earth.

But today, The Rebel’s Clinic will more likely be read through the events in the Middle East, following Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October and the IDF’s pulverisation of Gaza. As Geoff Shullenberger put it in his review of Shatz’s book for Compact:

In the wake of Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel, aphorisms by Fanon—such as “Decolonization is always a violent phenomenon”—circulated widely on social media, and debates over decolonization, settler-colonialism, and related concepts spilled from the seminar room into the streets. But this renewed relevance doesn’t only derive from the fact that the Jewish state is often derided by activists as a vestige of Western colonialism, or that the Palestinian cause is a remnant of the international liberation movement Fanon championed. Just as important is the broader context in which the Hamas onslaught occurred: the first coordinated challenge to the Western-led order since the end of the Cold War, by a constellation of powers arrayed around Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran.

The multipolar world that Shullenberger alludes to is not one that Fanon would have recognised. The rising powers of the global south are now capitalist powers, including China, and sometimes highly reactionary powers, such as India. A challenge to the western-led order, sure, but hardly one that is being mounted outside of or against the civilisation of world capitalism. Foreign capital continues to flow into India, for example, and is gratefully received by Narendra Modi’s autocratic regime. This mutually beneficial relationship is something Fanon would have recognised:

The national bourgeoisie turns its back more and more on the interior and on the real facts of its undeveloped country, and tends to look toward the former mother country and the foreign capitalists who count on its obliging compliance. As it does not share its profits with the people, and in no way allows them to enjoy any of the dues that are paid to it by the big foreign companies, it will discover the need for a popular leader to whom will fall the dual role of stabilizing the regime and of perpetuating the domination of the bourgeoisie.

What Fanon would also have recognised is how the people who have led many of these resurgent post-colonial societies in Africa and Asia have often failed to avoid what he called “the pitfalls of national consciousness” and have piloted their nations to ruin. In a devastating passage in The Wretched of the Earth on the “national bourgeoisie”, Fanon writes:

Seen through its eyes, its mission has nothing to do with transforming the nation; it consists, prosaically, of being the transmission line between the nation and a capitalism, rampant though camouflaged, which today puts on the mask of neo-colonialism. The national bourgeoisie will be quite content with the role of the Western bourgeoisie's business agent, and it will play its part without any complexes in a most dignified manner. But this same lucrative role, this cheap-Jack's function, this meanness of outlook and this absence of all ambition symbolize the incapability of the national middle class to fulfil its historic role of bourgeoisie. Here, the dynamic, pioneer aspect, the characteristics of the inventor and of the discoverer of new worlds which are found in all national bourgeoisies are lamentably absent. In the colonial countries, the spirit of indulgence is dominant at the core of the bourgeoisie; and this is because the national bourgeoisie identifies itself with the Western bourgeoisie, from whom it has learnt its lessons. It follows the Western bourgeoisie along its path of negation and decadence without ever having emulated it in its first stages of exploration and invention, stages which are an acquisition of that Western bourgeoisie whatever the circumstances. In its beginnings, the national bourgeoisie of the colonial countries identifies itself with the decadence of the bourgeoisie of the West. We need not think that it is jumping ahead; it is in fact beginning at the end. It is already senile before it has come to know the petulance, the fearlessness, or the will to succeed of youth.

What I appreciated most about Shatz’s biography is the focus on Fanon’s psychiatric work and how his theories about mental illness, distress and the human psyche, enriched by his engagement with French existentialism, as well as his experiences working in hospitals in France, Algeria and Tunisia, formed the subsoil from which his thoughts on racism and anti-colonialism emerged.

It is also his work as a doctor specifically, as opposed to his life as a militant-theorist of national liberation, that has had the more enduring influence in Israel-Palestine. As Shatz writes in the Epilogue:

The most faithful practitioners of clinical Fanonism today are psychiatrists in Israel-Palestine, where the occupation has severely affected the mental health of Palestinian citizens and colonial warfare has produced an abundance of mental disorders among both Palestinians and Israelis. Fanon himself never addressed the question of Palestine. But, as the Palestinian psychiatrist Samah Jabr puts it, “his prophetic insights remain a source of inspiration to Palestinians,” since he understood that colonial “subjugation is not only political, economic, or military” but also “profoundly and inherently psychological,” and that the “struggle for justice and the struggle for mental health” are inseparable. In their applications of Fanon, Jabr and her Israeli colleague the psychiatrist Ruchama Marton, the founder of Israeli Physicians for Human Rights, have mounted a sharp critique of Israeli psychiatry, exposing its complicity with the Israeli army, and its racist assumptions about the Arab mind.

The Rebel’s Clinic is a welcome corrective to the vulgar Fanonism that has been embraced by certain factions of the left, and is a testament to the essayist’s commitment to a style of writing that he has honed over the last few decades.

I met the 51-year-old American writer in Bloomsbury last year to discuss his earlier book, Writes and Missionaries. Although Shatz is also known for his work on music, especially jazz, the contents of these essays are weighted entirely in favour of his other interests in the history and politics of the Middle East and North Africa, French and American literature and theory, and post-war European cinema.

Unlike the intellectuals he critiques – all of whom were born between the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the establishment of the French Fifth Republic in 1958 – Shatz is working at a time of unprecedented textual abundance. “We are,” Richard Seymour observes in The Twittering Machine (2019), “abruptly, scripturient – possessed by a violent desire to write, incessantly”. Social media posts, emails, WhatsApp messages, journal articles, Wikipedia entries, news and opinion websites, and proliferating Substacks – there is an endlessly accruing mass of e-words, often produced for free, and ready for chatbots to simply scrape up and regurgitate back to us. As Justin EH Smith asked in a 2019 piece for The Point, under such conditions, “is there any way to intervene usefully or meaningfully in public debate”? Is there a serious role for the essay in the age of mega-text? Do writers like Shatz, and the intellectuals he seeks to rescue from “the enormous condescension of posterity”, even matter?

Born in 1972, Shatz grew up in Massachusetts. His parents – a lawyer and an educator – “are liberals in the old-fashioned sense,” he said, “people who believe that America should have a second New Deal and aspire to a genuine social democracy and who came of age in the era of both civil rights and the protests against the Vietnam war”. The rudiments of a Jewish education, which his parents gave to Shatz largely to inoculate him “from the temptations of fanaticism”, existed alongside a predominately secular upbringing, where issues of the New Yorker and NYRB sat alongside well-thumbed copies of Isaac Deutscher’s The Non-Jewish Jew, as well as books by Fanon, James Baldwin, and Malcolm X. “Neither of my parents was a radical,” Shatz explained, “but both recognised the importance and legitimacy of a radical tradition, and these sorts of books had an electrifying impact on me as a teenager”.

In 1990, Shatz began his undergraduate studies at Columbia University, where he studied French thought with Sylvère Lotringer, the founder of the publishing house Semiotext(e), as well as the historians Barbara Fields and Anders Stephanson. But his true alma mater in a sense, at least with respect his eventual career in letters, was arguably The Nation, through which he discovered journalists such as Christopher Hitchens and Alexander Cockburn.

It was Victor Navasky, a liberal with a fondness for the American communist tradition, and editor of the title between 1978 and 1995, who promoted outspoken heretics and troublemakers (and former NS luminaries) like Hitchens, Cockburn, and Andrew Kopkind. He also made Edward Said the magazine’s music critic. “It wasn’t just that the articles were politically passionate and irreverent,” Shatz recalled, “it’s that the contributors to the magazine were arguing among themselves in the letters page. And the letters page was always, for me, the most exciting section of the magazine because you saw these well-trained polemicists with fancy British educations jousting with each other”. For a young reader, instinctively progressive but footloose between the traditions – “I didn’t know if I was a Trotskyist or New Leftist” – the Nation was an archetype for how to give short shrift to ordinary judgements.

Shatz’s own style doesn’t resemble the free-wheeling, slash-and-burn invectives of Cockburn & co. Nor does personal ideology prevail over sobriety and scepticism – “an insistence on the autonomy of one’s own judgement,” as Shatz defines it. He avoids exfoliating his subjects of their personal rough spots or judging them against any kind of moral balance sheet. Michel Houellebecq’s comments on Islam are as ugly as his looks; Chester Himes’s attitudes towards women were detestable; Alain Robbe-Grillet was a literary pornographer and “resident psychopath in the republic of letters”; Claude Lanzmann was a self-flatter who championed Israel’s forever war on Palestine; and Said, thin-skinned and petulant, was an insufferable prima donna. None of them were especially happy.

But Houellebecq became the ur-novelist of post-political alienation; Himes surpassed his peers in the force with which he denounced America as a place without redemption; Robbe-Grillet reinvented the French novel; Lanzmann’s cinematic epic on the Holocaust, Shoah, remains a signal event in the history of European culture; and Said’s Orientalism inaugurated a runaway tradition of scholarship (and political accusation) that seems destined to never end.

Shatz’s view, somewhat unfashionable today, is that “to explain is not to excuse”, and that “it is impossible to study intellectual history without suffering from heartbreak from time to time”. Caricatures may travel better than portraits, the French intellectual and revolutionary Régis Debray once said, but they always win an expensive victory over understanding.

He may be drawn to radicals but Shatz’s approach to writing about them is closer to those anti-missionaries – Raymond Aron, Léon Blum, and Albert Camus – that the historian Tony Judt gently coddled in his book The Burden of Responsibility (1998). “There’s definitely some truth to that,” Shatz said when I pointed this out to him. “Although my original lecture in 2014 was titled ‘Writers or Missionaries’, when I entertained some sort of binary in which you have to align yourself with one or the other, the book is called ‘Writers and Missionaries’, suggesting that we’re always both depending on the occasion and subject at hand. But my political id is more missionary and my superego is more with intellectuals like Blum and Camus”.

Shatz is aware that the “responsible” writers Judt praised, especially Camus, could not see beyond the present while missionaries often see beyond the present, even if, in the midst of doing so, they fall prey to delusions. “Sartre had his share of errors,” Shatz explained, “but he understood decolonisation in Algeria better than Camus did. He may not have written in the register close to my own, but the responsible intellectuals do not always have a greater grip on historical truth”.

Shatz has been reporting from Algeria and other parts of North Africa and the Middle East since the early 2000s. His interest in the Middle East, especially, began after the outbreak of the first intifada in late 1987, when Israeli soldiers fired rubber bullets into unarmed demonstrators – events that were reminiscent of the repression in South Africa, and which shattered the idea of a humane democratic sanctuary for a long-suffering people. “My parents weren’t Zionists,” Shatz said, “and had never gone to Israel and were repelled by Israel’s increasingly religious character and the emergence of the settlers. Still, a certain residual sentimentalism lingered and in a passive way I absorbed it. The intifada, reading Said, Chomsky, Deutscher and Simha Flapan’s The Birth of Israel (1987), and meeting Arab students at Columbia ended that”.

There is no overarching thesis to Shatz’s work, but in the synergy of interests and concerns – black and anticolonial thought; negritude; the bearing of European imperialism on the life-worlds of thinkers who made their homes in the west; the enduring fallout from the Jewish catastrophe in Europe; the legacies of empire in France and the Arab world; Jewish dissident writing; the politics of jazz – one discerns the import of Shatz’s oeuvre, that, as Adorno put it, “the splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass”. Those who have witnessed or been on the receiving end of its power are best placed to illuminate the west’s hypocrisies and what Fanon called its “obnoxious narcissism” - writers from the Third World as the great dragomans of the First.

As Sartre wrote in ‘Black Orpheus’ (1948), “The white man has enjoyed for three thousand years the privilege of seeing without being seen … today, these black men have fixed their look upon us and our look is thrown back in our eyes”. Shatz’s essays, then, might be read profitably alongside the contemporary work of Pankaj Mishra, scholars of black anticolonial thought, such as Adom Getachew, Musab Younis and Kevin Ochieg Okoth, activist-writers like Verónica Gago, as well as those, such as NYU professor Nikhil Pal Singh, who have highlighted the affinity between American war making abroad and race making in the homeland.

And what of the future of the intellectual? Thunderstruck by political revolts on the right and left, and momentarily stunned by a global pandemic, the Anglo-American intelligentsia appears exposed and stupefied in the present conjuncture. The floundering commentariats of the west evoke James Baldwin’s observation that “the white man’s world, intellectually, morally, and spiritually, has the meaningless ring of a hollow drum and the odour of slow death”.

A transformation is underway. The new non-aligned movement of the global south, which unlike its Cold War predecessor is capitalist and driven more by pragmatism than by moral or revolutionary principles, is leveraging great power competition between China, Russia and the US to secure a more advantageous position in the global order. It is also in the global south, and those poor regions within the advanced economies of the west, where the impact of the climate crisis will be felt most severely. Do the dominant concepts inherited through the ages – of freedom, equality, solidarity, open society, justice, sovereignty, citizenship and the nation – still provide us with the means to imagine alternative futures in the age of climate emergency? Do we need a new Enlightenment for the Anthropocene?

It is within the teeth of that contradiction between rising power and deepening precarity that thinkers, activists and politicians of the global south - the descendants of Fanon - will be forced to reckon with this question most urgently. Western thinkers will remain essential interpreters of the world; intellectuals of the global south will be the ones who change it.

One of the books I’ve been recommending since its publication in 2022 is Linda Kinstler’s Come to this Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends. So it was a thrill to work with her on this review of Ukrainian novelist Tanja Maljartschuk’s book Forgottenness:

Originally published in Ukrainian in 2016 as Zabutiya, a word that describes the state of being forgotten or overlooked, of inhabiting oblivion, Maljarschuk’s novel was named Book of the Year by BBC Ukraine on its release. It documents the disorienting experience of witnessing irrecoverable erasure in real time. Faithfully translated by Zenia Tompkins, it is an unsentimental, unsparing account of the force of historical destruction and imperial domination. “Is it possible to kill time? To destroy it? To wipe it out of existence? To dig up the graveyards and pretend no one had ever been buried there?” Maljartschuk writes. Her English-language readers might anticipate a defiant answer, a resolute commitment to warding off oblivion and chasing away those who seek to erase the past. But Maljartschuk’s novel succeeds because she defies this expectation: her narrative refuses to indulge in the easy, appealing desire for a triumphalist future, for a future from which nothing has been erased and no one has been lost. Instead, she addresses her own question with brutal honesty: yes, she suggests, it is possible to kill time and to “wipe out” undesirable histories, and it is through a studied commitment to obliteration that empires and colonisers have, for centuries, seized land that was not theirs to take.

My timeline has been dominated these past few days by the harrowing footage of Aaron Bushnell, a young US airman who self-immolated in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington DC late last week. He was protesting the US’s role in Israel’s military strikes in Gaza. Richard Seymour will be writing on this in the coming days, but Noah Kulwin, the American journalist and co-host of the political history podcast Blowback, sent this short reflection on Bushnell to me, which I wanted to publish here:

My friend Daniel Hale, a former NSA analyst, was recently released from prison. He served 34 months for whistleblowing on American war crimes, having leaked classified documents regarding US drone warfare, which prosecutors called a violation of national security. After the news broke on 25 February that a 25-year-old US Air Force engineer, Aaron Bushnell, had set himself on fire in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington DC while screaming “Free Palestine!”, Daniel texted me about it.

Like Daniel’s actions, Bushnell’s decision to set himself on fire and broadcast it on Twitch (where it was swiftly removed) was political. “I will not be complicit in genocide,” Bushnell says to the camera before taking the final measures to ensure the fullest truth of that statement. According to his LinkedIn profile, Bushnell worked in managing the IT infrastructure of the Air Force, a task that conceivably put him on the virtual frontlines of America’s support for Israel in its campaign against Gaza.

Self-immolation as a protest tactic is fairly alien to the US, with the notable exceptions of Brooklyn environmentalist David Buckel (2018), anti-Vietnam War activist Norman Morrison (1965), and a still-unnamed demonstrator in Atlanta who attempted to set himself on fire in December last year in protest against the Israeli government.

In other parts of the world, the spectacle of self-immolation is regarded as an ultimate test of a resistor’s conscience. Writing for the New Yorker in 2021, the journalist James Verini traced its history from ancient Byzantium to Cold War Tibet and Vietnam, to the 2010 opening of the Arab Spring in Tunisia.

Viewed in this context, Bushnell’s final act can be interpreted as a historical dagger thrust into an American underbelly made soft by distance from the cruelties its government inflicts abroad. The significance of this is not lost on the victims of those cruelties - in Yemen, for example, some have even given Bushnell the honorific of "Haroun Al-Amriki."

Daniel felt a similar reverence for Bushnell, and also some frustration at the rational decision (likely taken to avoid a Twitter/X content violation) to blur out the moment when he died.

“I must admit that in part I’m saying that because I feel a strong sense of solidarity with his protest. There have been many times I’ve thought of doing just that, and I wouldn’t want it censored in any way,” Daniel wrote to me.

I responded that the video was most likely blurred because otherwise it wouldn’t have been posted at all, whereas users can marinate in other kinds of gory content — such as the destruction of homes, schools and hospitals in Gaza since 8 October – without drawing the ire of Musk’s threadbare content moderation. Or as Daniel put it, “They don’t pull Palestinian deaths cause those aren’t seen as the same.”

What sets Bushnell’s self-immolation apart is that it is among the first such actions protesting American military policy that was recorded and distributed to the public, with only the censorship of that soft blur over his burning corpse at the minute of his death. Norman Morrison’s death in 1965 was not recorded for the American public, which is too bad, because people in the US masses almost universally experience anti-imperial martyrdom as the province of the mentally ill or the non-white Third World. An action of men such as the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, who set himself on fire in 1963, and the press photo of which won accolades and is now the harrowing reference point for any American considering the war in Vietnam.

I did not want to look at the uncensored photos of Bushnell’s body at first. But Daniel asked me if he could share the images anyway, so that I could draw my own conclusions. I agreed.

What the blur leaves out is this: the flame consumed Bushnell from behind, and whatever accelerant he used caused the fire to leap twice as high as Bushnell’s actual height. Stilled by shock, his strong nerve, or both, Bushnell is consumed and standing high for a moment. Then he moves to his left, and the wind blows, and the flames are blown back to reveal a perfectly blackened upright body. Cuffs of flame where his pants have burned away show coal-coloured skin.

Then Haroun al-Amriki’s body meets the peace of the cement, where two police officers or armed guards approach him. One of them has his weapon drawn and instructs the inert body on the ground to get on the ground and not move. He died Sunday night, volunteering his life to show the havoc America and its allies bring to people beyond the borders of the homeland. “I ask that you make sure that the footage is preserved and reported on,” he wrote in a message the morning of his sacrifice. The least we can do is not avert our eyes.

Readings from the NS

“Quinn is a professor of ancient history at Oxford, and year after year she reads applications from students saying dutifully that they want to study classics to familiarise themselves with the roots of Western culture. Wrong, she says. This book is a reminder of how much more widely they need to look.” Lucy Hughes-Hallett reviews Josephine Quinn’s How the World Made the West: A 4,000-Year History, a book I can’t wait to read myself.

Reading elsewhere

Tobi Haslett, ‘Magic Actions: Looking back at the on the George Floyd rebellion’, n+1, Issue 40, Summer 2021. In the footnotes to The Rebel’s Clinic, Shatz describes Haslett’s essay as an example of those “Fanonian celebrations of violence” that were inspired by the George Floyd uprising. I think it’s also one of the best pieces of writing to have emerged from that moment.

Howard French, ‘The End of Françafrique?’, Foreign Policy, 26 February 2024. An insightful piece on the uprising against Paris in the Sahel, which is evidence of a renewed pan-Africanism, as the leaders of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger challenge other African countries to tear down the barriers that divide them.

Corrections

Last week, I described Alex Hochuli’s essay for American Affairs as “the latest” of those post-mortems on the millennial left that have been published recently, including in the NS. Alex has gently reminded me that rather than his contribution being yet another (late) addition to this literature, he and his colleagues performed their dissection much earlier with the publication of The End of the End of History (2021). I can recommend it, as well as this event Alex did with Adam Tooze in New York to launch the book.

Thanks for reading. I’m off next week but will be back with more on 14 March.

— Gavin.

Subscribed to the NS quite recently and this newsletter has been an absolute godsend. Excellent work, Gavin!

Thank You muchissimo !!! - wish i had the chance to read much/many of those recommended 'His- & Her-stories' ( - passing by All the thyme - and ir-regularly dusting-off - a double-sided 'tryptich' showing Just Thát !! ) ..... - and More-Even - to find 'company' accross the (a) table to discourse those thoughts . But really - well - grazie molto , Gavin !!